Many visitors ask us what were roles for women and girls at Beckley Furnace and in the historic iron industry as well.

The first thing to consider is the period of time in which Beckley Furnace operated. In the 1800s and early 1900s, women were not permitted to vote in elections, and for the most part were not seen doing industrial work. By contemporary standards, it was an incredibly sexist age. While today we know that women can do manual work, often as well as or better than men — that it is more a question of individual differences than gender differences — in those days people assumed that women simply could not do the kind of work required at Beckley and other iron furnaces. That left men with the major roles in operating a blast furnace.

However, women and girl children still played a critical role without which the industry likely could not have functioned, and if it had functioned it would not have functioned in the way that it did.

Women

The basic roles women filled at Beckley were cooking, maintaining the household, raising the children, making and repairing clothes, and operating small farms. That is an impressive string of jobs, and they were critically important to the operation of Beckley furnace despite being done mainly in and around the worker houses, not at the furnace. Those were times when usually one family member, traditionally the man, was considered “the breadwinner” and worked outside the home. The rest of the family functioned as the support structure that permitted the person working outside the home to function working 12 hour days, six days a week.

Let’s look at the cooking task. The work at the furnace was physically demanding, involving heavy lifting and other strenuous activity. To be able to reliably perform this work over time, the men working at the furnace had to be incredibly strong, and to stay strong, they had to eat a lot of protein and good food. The women spent much of their time cooking to meet those needs. We’ve seen estimates that a furnace worker, particularly one who worked in the casting shed, might burn an incredible 4000 calories per day, day after day, week after week, month after month. That’s a whole lot of food to prepare, and in an age when there were no supermarkets, everything had to be cooked from scratch — and that’s a whole lot of work; a full-time job, in fact.

Maintaining the household meant more than running a vacuum around every few days — in fact, in those days, vacuum cleaners were only just being invented, and few families had one. Running the household included pumping the water or getting it from a well or spring, washing clothes in a wash tub using a washboard and hanging them on a clothesline, sweeping (in the early days, with a homemade broom), and consider that modern detergents had not yet been invented — so most of the scrubbing was done with lye soap, which was — wait for this — also made by the woman of the house.

Raising the children was taking place in an era when babies were born yearly as modern family planning had not yet been invented. This meant that the woman of the house was either pregnant or nursing a baby nearly 100% of the time — in addition to performing all of her other duties — which also included nursing anyone in the family who was ill, and in an age before antibiotics and when vaccines were very few, illness was commonplace.

Making and repairing clothes was necessary since money to spend on store-bought clothes was scarce. The woman might buy some fabric at the company store and cut and sew the clothes for the family from it, or alter clothes that the older children had worn to fit the younger ones. The men, doing hard manual labor all day, were also hard on clothes, requiring frequent sewing to patch of repair them. Without sewing machines, this was hand sewing.

Operating small farms is something that surprises many visitors today. The fact is that each of the worker houses looked much different back in the day. In the first place, there would have been chickens roaming the yard, possibly a pig or a couple of sheep or goats, and in some lucky families, a cow living in the area right around the house. What area wasn’t occupied by livestock would certainly have been used to grow vegetables to feed the family when fresh and to can or to put away for winter. So there were animals to tend, eggs to gather, cows to milk, occasionally animals to slaughter and butcher, and hay to store up for winter for the animals and food to preserve and store for the winter for the people.

Arguably, the work the women performed was both harder and more demanding of special skills than the work the men did, and it certainly was not confined to a 12 hour day or a six day week.

Children (Girls)

The girls, once they were old enough to help, did mostly the same things as their mothers. A wife could not be expected to cook for more than one man (and her family) by herself. But that left plenty to do around the house. The girls were usually involved in the other tasks as well, although they usually helped their mothers with the cooking. With their mothers already overworked, the girls generally helped with laundry, cleaning, and maybe took on some cooking herself if her mother had too much to do. There was also garden to tend, and some livestock to take care of. Virtually all families had chickens, many had a hog or two, some had a milk cow. Each of these creatures took time to feed and care for — and usually this fell to the girl children according to their abilities.

Additionally, as soon as a girl had younger siblings, much of the care of these babies and children fell to them, as the mother likely had another baby to nurse and care for in addition to her other duties. Of course there was school, too, although in many of the years that Beckley Furnace was active, an 8th grade education was considered more than enough for anyone, particularly a female, and, in an age before extracurricular activities, there were few distractions from the work at home for most girls. Housework was more important than homework.

One unfortunate fact is that we have very little in the way of documents about the roles of females, and most of what we do know is second hand — someone, usually a man, mentioning what the women might have been doing. The rest? Well, we have had to examine the evidence and draw conclusions. Women who were well educated enough to keep diaries likely were also members of families wealthy enough to have domestic servants, and thus did not have the work experience of the women who supported the workers at Beckley Furnace.

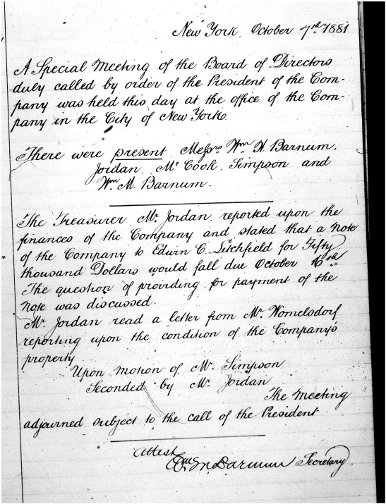

Also, it’s important to remember that while this may have been the life of females around a blast furnace, roles for women differed widely on the basis of their husband’s work. An ironmaster’s wife might have been expected to take an interest in the families of the furnace workers and offer hospitality when the big shots from Lime Rock visited. At a foundry, like the foundry Barnum and Richardson ran in Lime Rock, there would likely be a whole middle class made up of molders and other skilled trades, and the roles of women there might have been different, too. And finally, there were the few women who were married to the executives and the owners — and their lives were still different, but still demanding in their own ways.

Finally, this was an age when most middle class and all upper class families had household servants, most of whom were women, so their lives would have been different as well. The families of workers at Beckley Furnace would not have had household servants, however.

We’ll explore those roles in future posts…..

Like this:

Like Loading...